Benjamin Wolstein

2022-2023 Tanaka and Green Scholar

“Sumimasen,” I mutter as I stumble onto the Kyoto subway with my oversized suitcases.

What is the announcer saying? Am I on the express or the local train? Why did my Japanese

class cover units on single motherhood and climate change but not on reading signs? These

questions flurry through my mind as I make my way toward the hotel where the orientation for

the Kyoto Consortium for Japanese Studies will begin.

After a few days of orientation, I moved into my dormitory in a neighborhood in southern

Kyoto called Fushimi-Momoyama. Although it was somewhat removed from the downtown area

and a twenty five-minute train ride to school–Doshisha University–Momoyama had its own

charm and a lively shopping area. My dorm room was very comfortable and two meals were

served daily in the dining hall. Breakfasts were the same as dinners: some kind of meat or fish,

rice, miso soup, and pickles. I certainly did not miss toast or cereal!

On the first day of classes, me and some other students got lost on our way to Doshisha

University and arrived at Japanese class a few minutes late. This inspired our first class activity:

learning the Kyoto subway system. Despite our rocky start, Nakamura-sensei was extremely

helpful throughout the semester. She was always eager to answer my questions about situations

that arose outside of class, both language- and non-language-related. She also encouraged me to

start reading novels in Japanese after learning of my appreciation for Haruki Murakami.

Outside of the classroom, I began my search for a dojo close to school. I started practicing judo in New York a year and a half before going abroad, and was eager to gain the experience of practicing in Japan. I quickly found the Kyoto University Judo Club, which had a website in English for foreigners and is much closer than the place the Doshisha team practices.

Practices were six days a week for two and a half hours, and were very difficult. The warm up

lasted thirty minutes and included gymnastic-style movements that I had never seen before. We

spent a lot of time drilling moves over and over again, which greatly improved my technique.

Unfortunately, after about a month, spring break started for Japanese students and practices

moved to 9 a.m., the same time as my Japanese class. For most of my remaining time in Kyoto, I

could only attend practices on Saturdays. Even so, I was able to participate in two tournaments

with the team and observe two more.

I began my dojo search once again. With the help of Nakamura-sensei, I found a private club, Enshin Dojo, a short walk from campus. People of all ages and skill levels practiced at Enshin. Practices were not as demanding as Kyōdai’s, but I received more individualized instruction and focused more on the fundamentals. Until Enshin, my experience of judo in Japan had been very male-dominated, so it was a welcome surprise to study under two female senseis, Yamazaki-sensei and Shigitani-sensei.At first, it seemed like every time I passed Shigitani-sensei’s line of sight, she would correct some aspect of my technique. Eventually, thecorrections became fewer and fewer, and I was able to recognize many of the mistakes I was making myself.

Similarly, my language skills improved noticeably throughout the semester. At my first

judo practice, communicating was awkward and difficult. Toward the end, I had little problem

expressing my thoughts or understanding theirs, and was called upon as a translator when other

foreigners would visit the dojo.

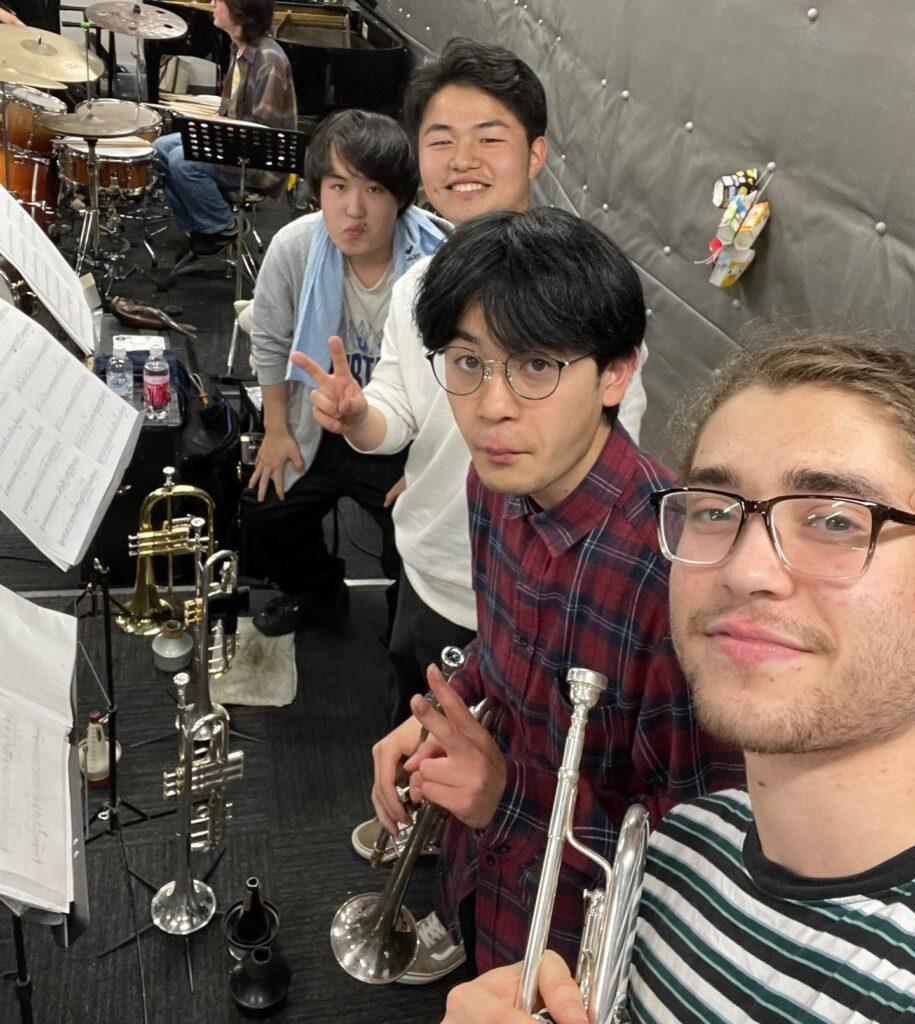

A little more than a month before KCJS ended, I met a student on the subway platform who was carrying a saxophone case. As a jazz trumpet player, I was curious to know if she was

involved in some kind of ensemble. As it turned out, she played in the Doshisha University Third Herd Orchestra, a jazz band whose videos I had seen on YouTube. I auditioned for and joined the group, but soon learned that the band practiced four times a week for eight hours at a time. Thankfully, they were very understanding about my class schedule, allowing me to join just a couple of times each week for three hours. The students were incredibly welcoming, offering me solos in the two concerts we played together. While at first I was worried about the time

commitment, I was really glad I joined the group for a short time. The band’s attention to detail

and commitment to the music was inspiring, and kept me motivated even when it was difficult to

practice in my dorm room. Moreover, the band’s focus on funk fusion was different from the jazz

I was used to playing in big bands at home and presented a new challenge for my playing.

One of my best memories was hanging out with my friend Kyohei, a drummer who I met

and played with a lot when he lived in New York. Seeing an old friend halfway across the world

made Japan feel more like home. Toward the end of my stay, Kyohei hired me for a performance

with his quartet at the Amagasaki City Hall in his hometown. We played two sets for an excited

crowd in a beautiful auditorium, and I helped as Kyohei held a workshop on the drums. The

students in the audience got to try out the drums, and a cameraman from the local news station

came to film a segment!

Looking back on my semester in Kyoto, I think my favorite moments were spent with

Japanese people over a meal (or drink). Whether I was with the Kyōdai judo team, jazz friends, or my language partners, I felt more connected to Japan when I experienced it with Japanese people and in the Japanese language. Of course, there were moments when things seemed extremely foreign, and conversely, moments when I felt as if the distance between our two cultures was insignificant. At first, I found myself going out of my way to show respect every

chance I could while in public. I would try to prove that I was one of the foreigners who

“respected” Japanese culture–that I could sit silently while on the train, that I could rattle off

culturally-appropriate phrases, and that I could wear a mask while indoors. But as the semester

progressed I came to believe that this was somewhat misguided; I could trust myself to behave in

an appropriate way, even in situations in which it was tough to know what to do. I realized that I

don’t need to worry about doing everything right or never causing offense–that being courteous

and showing a sincere effort is good enough.

This summer I am looking forward to self-studying Japanese and translating a Murakami

novel. I am very grateful to have received this scholarship and I hope to continue to be involved

with the Japan-America Society of Washington D.C. in the future!

Must check - WP faq support by geometricbox