Have you ever visited the centuries-old granite Japanese lantern located on the north side of Tidal Basin Lake and west of Kutz Bridge?

This stone lantern symbolizes the enduring international friendship between Japan and the United States established after World War II and was gifted by the Mayor of Tokyo in March of 1954 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Commodore Matthew Perry’s historic contribution to the treaty of trade and everlasting peace between the two nations.

“It was an act of appreciation,” said John Malott, former President of Japan-America Society of Washington DC “The Japanese … were extremely grateful to the United States for how we helped them after [World War II], that we were not an abusive victor. So, there was a tremendous sense of gratitude from the Japanese people, and they supported us.”

The Story Behind the Lantern —

The Edo Shogunate (江戸幕府), also called Tokugawa Shogunate (徳川幕府) was the last military ruling shogunate in Japanese history (1603-1868). It was originally established by Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康) and for 265 years established a political system under the strict control of the shogunate and divided the people of the country into four hierarchical classes – samurai, peasants, craftsmen, and merchants.

The lantern was originally carved to commemorate Tokugawa Iemitsu (徳川家光1604-1651), the third shōgun (将軍) of the mighty Tokugawa clan as well as one of the iron-fisted military leaders who ruled the Japanese islands in the centuries before the 1868 Meiji Restoration (明治維新) elevated the emperor from a ceremonial titleholder to actual power. The most famous ordinance in history, signed by Tokugawa Iemitsu, was the Sakoku policy (鎖国), which aimed at developing the domestic economy of Japan while shutting its borders to foreigners and halting foreign trade. Carved in 1651, the lantern stood for over 300 years on the grounds of the Iemitsu family’s shrine in what today is Ueno Park in Tokyo. A century after Commodore Matthew Perry convinced Japan to reopen international trade and end the Sakoku policy, the Japanese commemorated the resumption of Japanese foreign interaction by sending this Japanese lantern to the United States.

The Construction and Meaning of the Lantern —

The Japanese lantern stands approximately eight and a half feet tall and weighs two tons (4,000 pounds). Every detail of the lantern speaks to people with its profound historical and cultural significance.

Houju (宝珠)

The round knob at the top of the lantern, referred to as Honju, is shaped like a Buddhist holy relic. Like traditional Japanese architecture’s curved roof edge corners, Honju is created to dispel evil spirits and protect the rest of the lantern.

Kasa (傘)

Kasa translates to “umbrella” and serves to prevent the firebox beneath it from being affected by changes in weather conditions. The center of the front of the Kasa is carved with the Tokugawa family’s distinctive three-leaf heraldic family crest.

Hibukuro (火袋)

The lantern’s firebox has a square opening symbolizing the earth and is used to light the lantern each year. The shape of a crescent moon is carved on the northwest face of the firebox. Three dots on the southern face represent the Triad, a symbol deeply rooted in East Asian Buddhism. The three dots are also the heraldic symbol of the Matsura family, a branch of the clan that originally gave the lantern as a gift to the shōgun (将軍). On the northeast face of the firebox is a symbol that represents the sun.

Chuudai (中大)

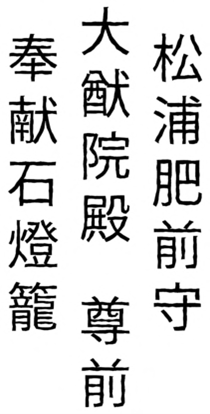

This is the main body of the lantern and has a blooming lotus flower design engraved on the bottom and top. On the front of the structure, we can see a string of faint text that records the 370-year history of the lantern: it was originally presented to Tokugawa Iemitsu on November 20, 1651 by Shigenobu Matsuura (松浦重信), who was a daimyo (大名) in present-day western Kyushu, Japan.

Kidan (基壇)

This is the bottom part of the entire lantern and its base. It has a hexagonal shape, and each side is carved with the pattern of a beautiful blooming lotus.

It is said that the lantern was originally part of a two-lantern set installed during Tokugawa Iemitsu’s funeral ceremonies at his family’s shrine, Ueno Park today in Tokyo. Even though Ueno Park’s lantern collection contains no matching lanterns, many of the published literature on the lanterns claim that the twin stands there to this day. One can imagine that the other lantern exists in another part of the world and serves to share with people its equally important historical significance.

Planning to visit the Japanese Lantern this Summer? Tag us on social media after you visit and share your experience with us!

References

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/cherryblossom/japanese-stone-lantern.htm

https://nationalmall.org/content/japanese-lantern

https://www.kurisu.com/project/japanese-lantern-washington-d-chttps://www.washingtonpost.com/history/interactive/2021/japanese-lantern-tidal-basin-cherry-blossoms/